70th anniversary of the Auschwitz liberation

- etaino

- Jan 26, 2015

- 6 min read

It is 70 years since the liberation of Auschwitz and as survivors gather for a commemorative ceremony I look back to my visit on a bleak winter day. These images were taken 20 years ago but have never left my mind.

The landscape is near monotone. The grass has faded to a dull yellow, the industrial architecture is grey and the sky even greyer. The Polish town of Oświęcim, just 60km west of Krakow, means little to most outsiders. However, it is better known by its German name, famous all over the world in fact. Unfortunately, its legacy is far from pleasant. Oświęcim is home to some of the most horrific memories of our century and the infamous Nazi workcamps of Auschwicz and Birkenau.

The horrors of the gas chambers in Auschwitz are something that will never be forgotten by those who survived the war or those who remember their dead from that time. But what about the rest of us? It's easy not to think about what happened, not to think about the brutality of the "Final Solution", to sweep the memories under the carpet of time. However, there are some things none of us should forget.

Travelling to see the remains of a place known only for its gruesome history may seem a little macabre at first. After a few hours it seems infinitely worse. Despite the passing of 70 years, the atmosphere of the camps is chilling to say the least and the shock of a visit is likely to affect you for a long time.

A "tour" begins at the centre in Oświęcim. A large car park now flanks the administrative buildings that have become an interpretive centre. From this angle the well kept yards and shrubbery harbour little resemblance to the gruesome interior. Inside the centre we sit to watch film coverage of the death camps and their eventual liberation. Now familiar images of cattle wagons overcrowded with frightened innocents begin the audio visual display.

The Nazi propaganda machine in full action eulogises about its efficient methods of extermination and its ambitious plans for an Aryan race. Endless streams of people seem to be herded from one area to the next, each time a little thinner, each time a little more despairing. Although the images are not new, they take on new meaning in this environment. The auditorium is silent as everyone contemplates the horror of the events.

We leave the auditorium and walk down a corridor full of stooping mannequins dressed in striped camp attire. The walls are adorned with thousands of mug-shots of ordinary people forced into prison uniforms and an extraordinary situation. It is impossible to fully comprehend what terrible crimes were committed here, impossible to understand the huge scale of these horrors. I am numbed by the sheer number of photographs. There is sensory overload and I cannot do justice to the memory of these people with my insufficient feelings of regret and despair.

A diary entry accompanies some of the photographs and it is these that give you some sense of the realities of Auschwitz. The personal stories of wives separated from husbands, children taken screaming from their mothers, old people herded naked through the snow. They make the clinical museum exhibits a little more personal, these were real people with families waiting somewhere and a whole story to tell. Looking back at the wall of photos the painful reminder comes that each heart-rending observation is only a small token of the thousands and thousands of similar nightmares that ended here.

Established in April 1940 in the pre-war army barracks on the outskirts of Oświęcim, Auschwitz was originally intended for Polish political prisoners but it quickly turned into the now infamous centre for the extermination of European Jews. In 1945 the retreating Nazis destroyed part of the camp in an effort to hide the evidence of their barbarous crimes. What remains however, is more than enough to convey the magnitude of the terrors. Most of the original buildings stand today as a bleak testimony to the camps' history.

I walk into the camp proper through the famous gates that proclaim Arbeit Macht Frei (Work Makes Free) and walk to the barracks along a high, intimidating, double fence of barbed wire. Altogether thirty prison blocks remain. The buildings spread in every direction and each one holds a display more moving than the next. One large room is piled high with suitcases from floor to ceiling, the next with pots and pans, then hairbrushes, then children's shoes. Endless lists line the walls, name after name of innocent prisoners, exterminated only for their ancestry. Outside, the camp is immaculately kept but this cleanliness jars against my conscience. How can these mounds of forcibly abandoned possessions be reconciled with the crisp gravel and flowering plants outside? Why should anyone's personal belongings become a museum exhibit?

Further on I approach an unmarked building, once inside there is little difficulty in determining its use. Two enormous boilers lay idle beside the open walls of a giant furnace. A solitary vase of flowers sits forlornly on the crude metal burner. When confronted with such instruments of death and destruction it is impossible not to reflect on your own life and its relative safety. How easy it has been, how little there has been to worry about. I realise it is only chance that has separated me from this time and place. I find it difficult to stay for long, the images are too real, too close to home.

Looking back at the camp as I leave, the simple brick buildings are made all the more sinister by their innocent appearance. As I walk down the road towards Birkenau I reflect on what I have just seen. For some reason I had never imagined myself here, never connected the image with reality. I know that from now on however, I will never separate them.

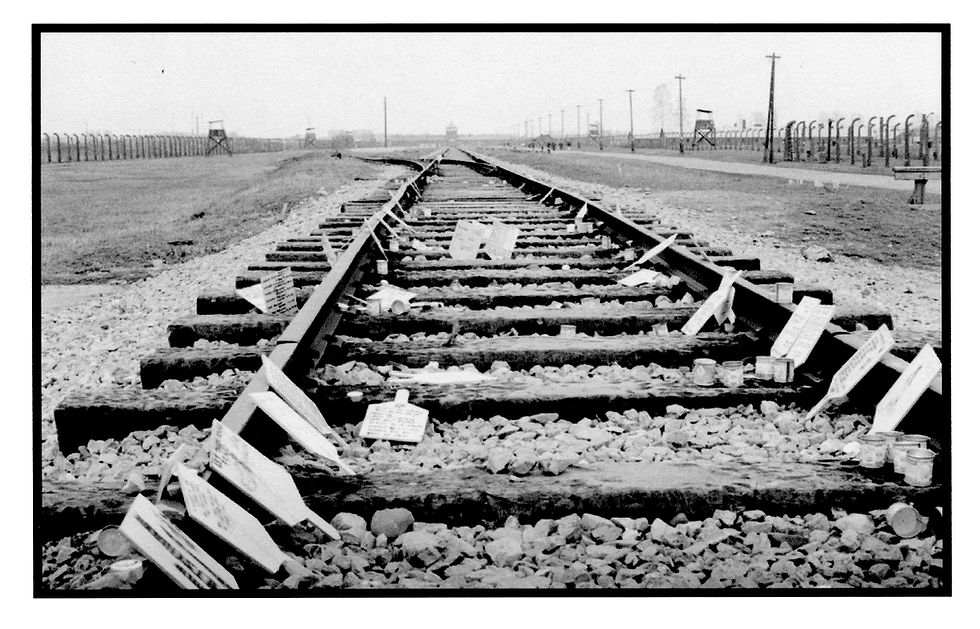

In 1941 the Nazis realised that they could not keep up to the speed of their own plans and the much larger Birkenau (Brzezinka - Auschwitz II) camp was built just 2km west of Auschwitz. The famous gates of Birkenau come into view long before I reach the site. On the flat, bleak landscape the railway track and the ominous gateway are difficult to miss. I walk towards the covered gate on railway tracks strewn with candles and placards with Hebrew inscriptions. I can't read the writing but I have no need to decipher this foreign script to understand its meaning.

If the remains of Auschwitz I had been clinical in their approach, Brikenau is nothing but reality. Vast, purpose built and efficient, the camp stretches for miles in every direction. It had over 300 prison barracks and four huge gas chambers complete with crematoria. The site has been left largely untouched since its abandonment in 1945. The barracks are falling down, the ground covered with mud and the sheer size and barrenness of the area, cordoned off with high barbed wire fencing and watch towers stretching almost to the horizon, gives some idea of the number of people who passed through this terrible place. Birkenau was the over-flow camp from Auschwitz to begin with but it soon became one of the largest process areas in the entire Nazi occupied territories.

The barracks are open and as bleak as they appear in every film they have ever been a part of. These crude brick and wood sleeping areas housed hundreds of thousands and prepared them for their final fate. Large, faceless and without a single comfort, the icy draught whips through the warped wooden doors and a small fireplace by the entrance could have offered little protection from the cold. It is a solitary candle flickering on one of the bunks that grabs my attention.

At the back of the site a monument to the dead stands with the ruins of gas chambers on either side. I would like to believe something like this could never happen again but our newspapers are still full of stories of atrocities carried out against totally innocent people. History, it seems, has taught us very little and those of us lucky enough to be safe from harm stand by at a distance and do little to help. The distance keeps us safe from reality. However, the imagery is far too real when standing at the gates of Auschwitz.

Comments